How we understand wordless stories

1 October 2025

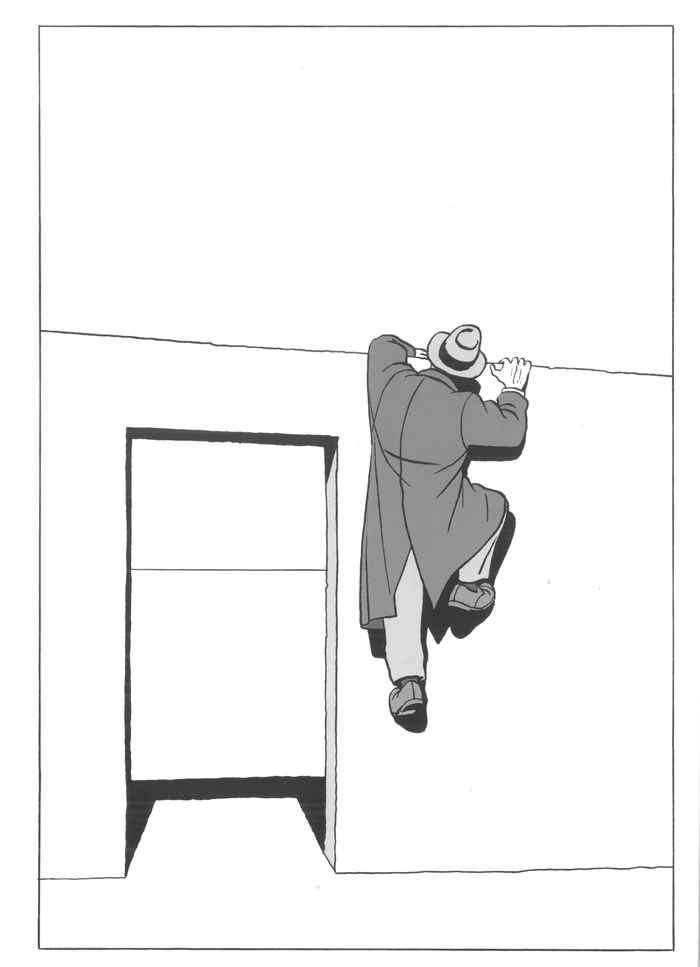

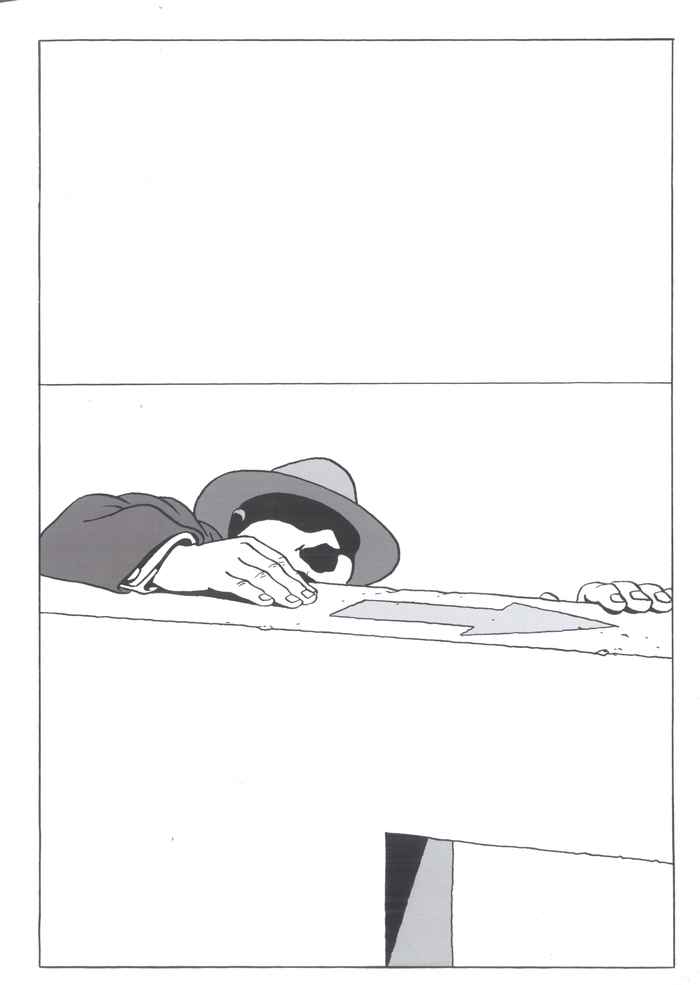

In Sens (232 pages), an anonymous traveller - a man in a long coat and wearing a hat - follows arrows that appear in many different forms: on walls, in footprints, as a raft, or even inside his own suitcase. Sometimes the arrows point in opposite directions, and often they seem to lead nowhere. Eventually, the man arrives at a field of arrow-shaped gravestones: a visual symbol of death.

Most comics, such as Tintin, Asterix and thos by Marvel , combine images with text, often in the form of dialogues. According to Forceville, Sens convincingly shows that a long and layered story can also be told without a single word. Readers, he argues, understand these images through their daily experiences in the real world and through their familiarity with story patterns and the ‘language’ of comics.

Daily experience and story patterns

Forceville explains that readers interpret a wordless story partly thanks to their knowledge of the world. ‘We recognise objects, people and events in drawings because of our everyday experiences in real life - often without consciously realising it,’ he says.

But readers also identify Sens as a story with a familiar structure: there is a protagonist with a goal, there are obstacles, and there is an outcome. Forceville: ‘A journey has a beginning, a path, and an endpoint. This applies not only to the main character’s literal travels, but also to his symbolic quest: he starts from a problem, overcomes obstacles, and eventually reaches some sort of solution.’

Sens demonstrates the power of communicating visuallyCharles Forceville - media scholar at the University of Amsterdam

Because the comic itself is graphically structured with a beginning, middle and end - and because we are familiar with such story patterns - we can follow the story image by image.

Comics have their own instruments to communicate

Forceville stresses that comics employ their own distinctive tools for conveying information to readers. ‘Just as a novel uses language that must be understood, a comic makes use of visual devices,’ he explains. ‘Movement, for instance, can be suggested by a character’s posture, or by lines that indicate speed or direction.’

Equally important is that the reader must actively fill in what happens in the space between two drawings, the so-called gutter. ‘In Sens, this often happens very subtly. If you look carefully, you’ll see that more changes between the images above than just the camera angle rotating 180 degrees.’

The power of visual language

With his analysis, Forceville not only shows how Mathieu’s graphic novel works, but also contributes to a broader understanding of how people interpret stories, even when told entirely without words. ‘Sens demonstrates the power of communicating visually. Visual communication has no grammar or vocabulary, yet even without these, important, complex things can be told.’

Publication details

Charles Forceville: ‘The JOURNEY metaphor in Marc-Antoine Mathieu’s graphic novel à (Sens)’, in: Language & Literature (2025). Go to the article