The street brought to life: movements of Amsterdam citizens in the 17th and 18th century

7 February 2022

‘We know a lot about old buildings. You can walk around in Amsterdam and then you really have the feeling that you are walking in an old city’, says Pierik. ‘However, the only thing you can still see of that are the buildings, not the people. What you don’t see is how they experienced this city in the past.’

In order to bring the historical streetscape to life again, Pierik conducted research into the the question of how the inhabitants of Amsterdam in the 17th and 18th century accessed the street. ‘Where they went to, what they did, how they did that. And in particular the difference between men and women.’

Accepted inequality

‘There was inequality in the period that I researched; no attempt is made to disguise that. In this period (1656-1791), the differences between people are viewed as the natural state of affairs.’ The expectation was that men could move through the world more independently and thus venture further afield. ‘That is something which we always assumed, but it has never been empirically analysed.’

Pierik based his research on notarial depositions of conflicts on the street: disputes between neighbours, dangerous parking situations with coaches, bar fights. ‘They are everyday conflicts, as a result of which they say a lot about how the street was, what happened on the street and who owned the street.’ By researching where witnesses involved in these conflicts lived, he was able to analyse what the mobility of the inhabitants looked like.

‘You also see that a keen eye was kept on the street, much more than now. The transparency between the home and the street was much greater.’ In the corpus, the historian found a deposition of a woman who took a walk with a man in the evening. ‘Years later, while she had been married for a long time, that man declared that nothing indecent happened there. All kinds of neighbours confirmed that then. They still remembered that!’

The street as telephone cable

The perception that the early modern woman was stuck in her house is far from accurate according to Pierik. ‘That is more nuanced: women were constantly active in their neighbourhood and also went through the entire city, although less than men on average.’

Being confined to the house was also not an option, because you had to leave the house for the smallest things. To buy something, but also, for example, to tell someone something. ‘In the same way we reach for our telephone now, at that time there was also a network of people who shared information with each other. They used the street as a kind of telephone cable. Running the home was also not an activity that you were occupied with the entire day and it was combined with all kinds of other work.'

There was no patrol that said: women have to stay home.Bob Pierik

Women therefore remained in their own neighbourhood slightly more than men, but not because they had to do that. ‘There was no patrol that said: women have to stay home, women have to remain in their neighbourhood. It was due to practical reasons: because they had their network there.’ Pierik did find one example of an old women from the Lutheran alms house who was given a kind of street ban. ‘She was punished with a kind of house arrest, because she went to the wrong pastor.’

Gatekeeping

In his research, Pierik discussed a phenomenon that he refers to as ‘poortwachten’ (gatekeeping): determining who is allowed to occupy space at a particular place. In the period researched, the boundaries between private space and public space were experienced and interpreted differently. ‘The pavement or the double door are examples of places between the street and the home, where the household claims a piece of street.’

In one of these depositions, a conflict is registered between a housemaid and her neighbour. The housemaid put her washing out to dry on the hay barge of a neighbour, but he was not pleased with that and picked a quarrel. ‘Then all the neighbours came outside who became angry with the neighbour and said: you are not using that hay barge at all, why can’t that the girl put her washing there? In this way, someone who had little power officially, a housemaid, had a claim confirmed by neighbours on the street. Or in this case even the water.’

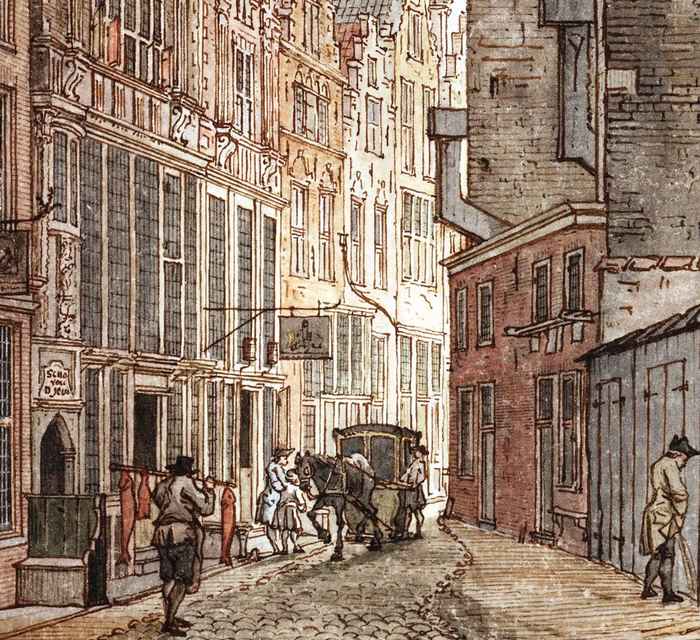

The closer you come to the canal houses, the more you see people withdraw from the street. They are literally elevated in coaches, have high pavements and even go to live further behind in their house. ‘I found a record of a conversation between the sawmill owner and a legal representative. The legal representative asks the sawmill owner to come inside quickly, because: “I don’t speak to people on the street or on the pavement”. That is a radical difference with the rest of the city, where everyone talks to each other on the street.’

The shock of the coach

The upper classes took up space, but cut themselves off from other people. ‘With a coach, for example; a gigantic claim of public space. We are so used to the fact that there are different road users with different speeds, but that was once an enormous shock, to the extent that people said: this can’t go on like this any longer, we have to ban that.’

Coaches were initially only able to drive at a walking pace and were not, in principle, for use in the city. They drove too fast, they crashed into people, they ran over children. Speeding fines were also handed out to coaches that went faster than a walking pace.

Men govern

‘Such a coach was only driven by men, so the perpetrators were all men. The victims were therefore women and children. Women had less access to that culture. Rich ladies were, however, allowed to ride in a coach as passengers, but never as drivers.’

‘Nowadays, horses are actually associated with women often, but in the 17th and 18th century handling horses was truly a man’s job. When it came to riding horses, that was referred to with a patriarchal metaphor as “regeren” (governing), explains Pierik. ‘In the 18th century, one of the best stablehands in Amsterdam died, the person who tamed all horses. The autopsy revealed that the stablehand was a woman. The shock caused by the revelation that women could also control horses was enormous.’

The only reason that he could practise two professions at the same time was because his wife also worked with him, but he received the reputation and name.

Pierik also found a note about a couple that worked on the street late in the evening. He worked as a night watch man and garbage collector, a combination of collecting garbage and patrolling the streets. His wife accompanied him. ‘The only reason that he could practise two professions at the same time was because his wife also worked with him, but he received the reputation and name. Women appear to be absent in the material, but if you read between the lines, they were just as likely to be involved.’