Vossius Seminar 12 May: Stefan Gaillard & Leendert van der Miesen

- Date

- 12 May 2025

- Time

- 16:00 -18:00

- Location

- University Library

- Room

- Vondelzaal (room C1.08)

Program

16.00-17.00h: Stefan Gaillard, Radboud University Nijmegen

Tracing the History of a Promise

Since its emergence, nanoscience has been accompanied by grand promises. Some of these have led to significant breakthroughs while others have ended in disillusionment. The infamous Theranos case, for example, was not merely an instance of fraud but also of repeated overpromising – a phenomenon not uncommon in scientific fields. Promises enable cooperation and mutual confidence, but, when broken, erode trust and credibility.

Despite the central role of predictions and promises in science, there is a surprising lack of methods to systematically identify and track them over time. Developing such methods would offer several benefits. It could help discourage repeated overpromising, provide insights into the trustworthiness of researchers and institutions, reveal whether journals, funders, and media correct or perpetuate hype, and shed light on stagnant or overhyped research areas.

My PhD research concerns overpromising in science, specifically focusing on conceptualizing what it is and developing tools to identify and analyze it. As part of this work, I have begun to explore methods for detecting promises and repeated overpromising in scientific texts. Using a corpus of nanobiology documents, we experimented with ways to extract and classify such statements.

While the approach shows promise in capturing repeated overpromises in relatively straightforward cases, it also highlights deeper conceptual challenges. One major issue is term and conceptual drift. Another challenge is managing the output of queries. The volume of hits can be overwhelming, making manual analysis labor-intensive. Still, these early explorations offer a useful foundation for more systematic approaches to analyzing scientific promises over time.

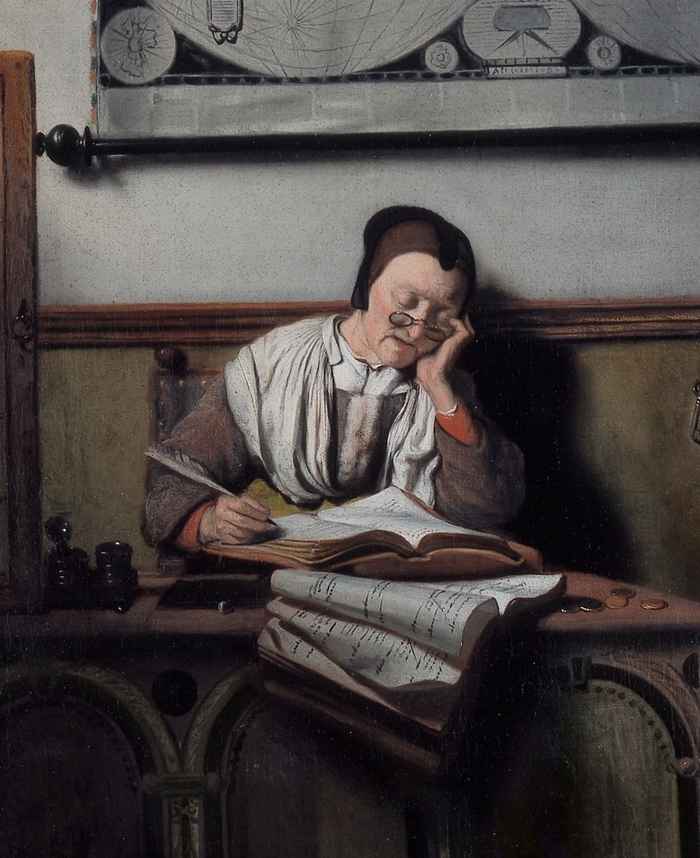

17.00-18.00h: Leendert van der Miesen, Vossius Fellow University of Amsterdam

A Sound Science: Drawings, Echoes, and the Making of Acoustics around 1700

In 1700 Joseph Sauveur defined acoustique as the science of all sounds, as opposed to music as the study of sounds that are pleasing to the ear. With this, the field obtained a firm position among the scientific disciplines and was there to stay. The establishment of acoustics is often told as a story of the incommensurability of musical questions with the study of sound as a physical phenomenon. The experimental and graphic practices of early modern scholars researching sound have not received a great deal of attention in this narrative. In this talk, I will focus on the role of experimenting with and visualizing echoes, the phenomenon of hearing a sound repeated. I will discuss the efforts of scholars in France, Italy, and England who made paper models of caves, traced geometrical lines in building plans, and visualized sound propagation through diagrams around 1700. This talk argues that the visualization of sonic phenomena was of fundamental importance in early modern acoustics but also highly contested.